The skirt is made up of three straight panels of 50" wide fabric, pleated into a waistband and finished at the bottom with a wide hem facing.

By 1865 skirts could be cut one of two ways - all straight panels all the way around (Each panel is the same width at the top and bottom.), or with gored panels (Cut wider at the bottom and narrower at the top for less bulk at the waistline and more volume at the hem.).

The 1864 ball gown in Patterns of Fashion II by Janet Arnold, which I referenced for bodice construction details, has a gored skirt. However, I knew that did not necessarily mean the 1865 ball gown I was recreating also had a gored skirt. I decided to read through the museum database description of the dress yet again to see if the cut of the skirt was referenced at all.

I was in luck! The (translated from Swedish) description read "Skirt: Consisting of eight straight lengths, seams machine sewn". My dream ball gown's skirt was cut with straight panels, so my reproduction would be cut the same.

In the 1860's fabric widths were narrower than they are today, thus the reason the original dress' skirt was comprised of eight panels to get the necessary fullness. After looking at the skirt dimensions (also shared in the museum database's description), I determined, due to the width of the fabric I was using, my skirt only needed to be comprised of three straight cut panels.

So, after determining how long the skirt would need to be to go over the hoop skirt and reach the floor, I cut three panels of fabric, and seamed together the selvedges.

This gave me one big loop of fabric, which I then hemmed with an extra deep (probably deeper than it needed to be) hem facing of green and white polished cotton. (I actually have about 6 yards of this polished cotton, so you can expect to see it used for an awful lot of hem facings in the coming years.)

Once the fabric "loop" that would become my skirt was hemmed, it was time to adjust the skirt to the exact length it needed to be. To do this, I measured up from the hem and marked the correct length at the top of the skirt. (1860's skirt length was adjusted from the waist, not the hem.) 44" in the front, and slightly longer in the back.

Once the length was marked all the way around, I folded the excess fabric at the top down to the inside of the skirt and pressed that top fold in place.

Then I threw the gigantic loop of fabric on my dress form, over the hoop skirt. (I stuck my dress form on top of the dining room table at this point to (hopefully) keep the skirt free of dog hair, which quickly accumulates on the floor despite regular sweeping.) It was time to begin pleating.

Yet again, I examined the pictures of the original dress to figure out the exact pleat arrangement. Then I did my best to replicate it. There are 8 box pleats in total around the top of the skirt. At the center front these are single pleats. All the other pleats are double pleats.

Once the skirt was pleated, I whip stitched it onto the waistband.

The black cat (Susie Q) "helped" by laying on top of the skirt in my lap the whole time.

Once the skirt was attached to the waistband, my sister tried it on over the corset and hoop skirt just to make sure it fit properly. It did! (Since the finished dress will more or less be shared by my sister and I, half the fittings during construction were done on her, and half on me. I am pleased to say the finished dress fits us both - just as intended!!)

Now it was time to add the crowning glory of the whole dress - the lace swags - to the skirt!

Back onto the dress form on the table the skirt went, and out came the lace.

First, I trimmed the excess netting off the scalloped border of the lace.

Then I folded the lace in half lengthwise, lining up the borders, figured out how deep I wanted the lace to be, and cut the folded edge off. This gave me two strips of lace with a border on one edge.

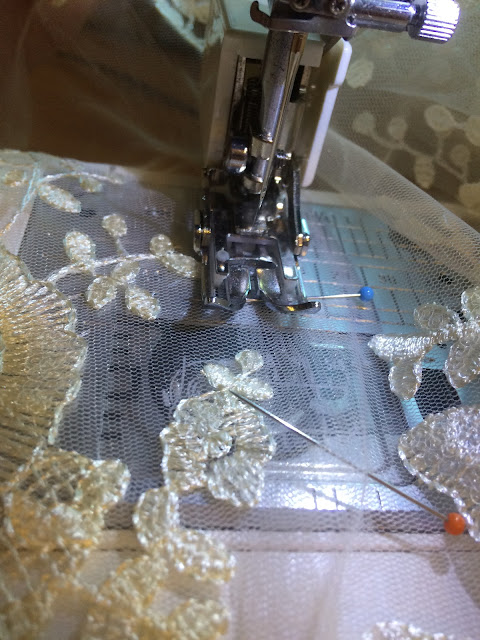

I overlapped the ends of the strips of lace, lined up the motiefs, and top stitched the ends together using clear/invisible thread on the sewing machine.

Yes, clear plastic thread is in no way, shape, or form, historically accurate, but neither is sequined lace. With this dress I'm aiming more for "correct overall look and construction", not "perfectly historically accurate materials". Perfectly historically accurate materials were way out of my price range for this project.

Once the ends were sewn together, I had a 6 yard "loop" of lace (made from 3 yards of double-bordered lace), ready to attach to the skirt.

I marked the "quarter points" of the lace, and pinned those to the "quarter points" of the skirt, inbetween the box pleats, about 20" up from the hem.

Then I went around and pinned the "eighth points" of the lace to the "eighth points" of the skirt - between the remaining box pleats.

Finally, I tacked all the points with a few small stitches, and I was ready to make the last part of the skirt - the bows!

For the bows, I cut eight 20" long, 6" wide strips of moire. Then I did little hand-rolled hems at the top and bottom of each strip. Next, I fringed the ends by pulling out about a centimeter's worth of weft threads.

The hemming and fringing was tedious and took a while.

Once that was done, I folded each strip into a bow shape and tightly wrapped a 1" wide strip of moire around the middle of the "bow".

Finally, I sewed the bows onto the skirt where the lace was tacked in place, and the skirt was done.

Not only was the skirt done, the whole dress was done!

This pink and lace ball gown, that I'd been dreaming of making for years, was finally, actually, amazingly, done!!

All done, and ready for my sister to wear on stage as Mrs. Fezziwig in A Christmas Carol next weekend!